Cecilia Jiménez Ojeda

Skrubbsår. En oppvekstfortelling.

03.04 - 16.05.21

Architecture can be abrasive. I gave up architectural critique for Lent, and I intend on keeping the fast going.. Therefore this text won't be lamenting vitriolic office buildings creating wind tunnels, blocking the sea view and deflecting the sun from common pedestrians. Nor is this my program on socially unjust city planning. It's a matter of fact. And I have the scabs to prove it. Cecilia Jiménez Ojeda's solo show Skrubbsår. En oppvekstfortelling awoke a dormant knowledge I hadn't considered in a while. Namely how some buildings seem to have a life of their own, and that certain among those seem to be ill-willed. Some buildings have greater ambitions than providing its inhabitants and visitors with shelter, security and warmth. Rather than matrixes, they are mazes. Moody ones at that, and unpredictable. Riddled with traps, danger zones and ever-changing, often inexplicably blocked escape routes. They fill the unprepared meanderer with suspense, heightened alertness and a sense of disembodied aggression, ready to spring into action.

The malicious building I know most intimately seemed designed for causing harm. Sometimes the damages were mere bumps and bruises after having slipped on the wet linoleum the janitor kept immaculately waxed while the rest of the building deteriorated. Often there were sprains from the ravenous bannisters, snipping at – and catching – our flailing limbs as we rushed by. Or they were nosebleeds from the humiliating practice of trash ambushes, where the unlucky were dumped headfirst into the refuse containers in the basement – the very belly of the beast. The building was plated with asbestos. Grime running down the unwashed façade made it appear as though the windows were wasting their mascara weeping. The house was a brusque, but practiced teacher. We quickly learned which floors to avoid when one of the tenant's moods echoed throughout the staircase, and where to flock to receive winegums on the 12th of every month, coarse sugar granules mangling our mouths. We read the scents seeping out from underneath the apartment doors like bulletins, sharing vital intelligence among ourselves as we ran past other groups in the endless corridors. No new locks or leering lodgers could keep trespassers out. The building had the suburb's only elevator, the suburb's most gregarious drunks, it was the only place bearing any semblance to urbanity, and it had a broken skylight from where we could squeeze out onto the roof. If entering happened at our own risk, it was a calculated one. For better or worse, the children ruled the building. We learned how to stay close to the walls, keeping our chins tucked and our heads low, our strides inaudible.

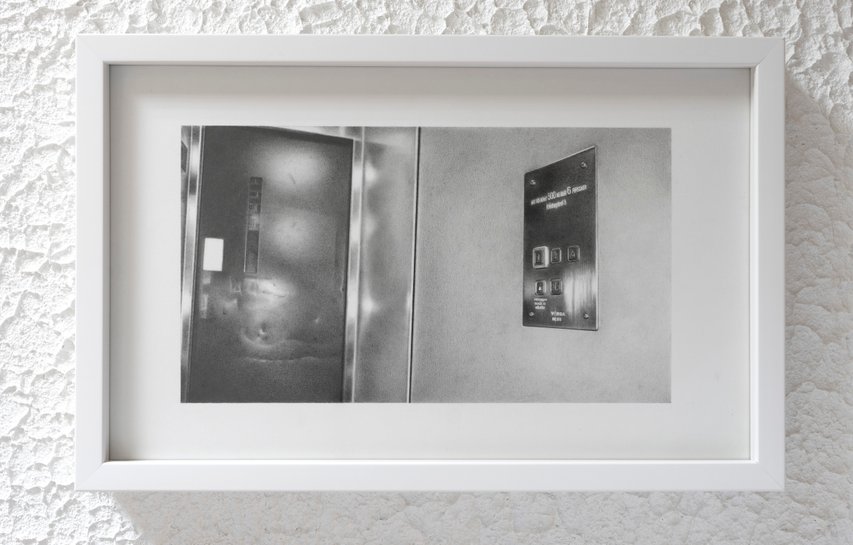

From the street, Cecilia's white wall modules look deceptively minimalist. The walls are modelled after the corridors in the apartment building where the artist grew up in Borås, Sweden. Image searches reveal few photos of the suburbs, with its rigid grid of uniform housing, and plenty of photos depicting Swedes' penchant for the grandeur of times passed. Cecilia installed her works in strict rank facing the back corner of the space, like a queue of dunces. The wall modules are covered in textured acrylic paint, so sharp and pointy it could make you wince. In conversation, we hypothesized what the purpose of the textured paint might be. The material's willingness to be caked on may be an advantage if one wants a low-maintenance wall surface, but it seems a nightmare to keep clean, dust, repaint, or live in any proximity to. During Cecilia's childhood, the fanged walls served another purpose altogether. As if it were nothing more sinister than a game, loitering children would tackle one another as they passed one another in the corridors. Knocking each other off-course and into the textured walls at high speeds, strips of skin were flayed from the victim. The spaces between the modules are narrow. Shuffling into the gaps to study the artist's small-scale, detailed drawings, I'm viscerally aware of the wall behind me. Its extended fangs had snagged me more than once. The drawings are based on photographs she took as an adult, revisiting the area she grew up in. They're hung high enough not to be knocked off the wall, should a reenactment of the particular childhood memory be played out. They depict a bodega, the irrelevant containers blurred only to focuson more important matters; an elevator with notices in sans serif-fonts on the banged up steel walls; and a familiar non-area which has served as a backdrop for many a first kiss, beer and other things we're not at liberty to divulge: the underbelly of a highway bridge. The scenes are unpopulated. Only the artist's gaze, acting like a peculiar surveillance camera, and her inveterate skill as a drawer animate these candid snippets of seemingly uneventful everyday life.

They say the olfactory is the shortcut to memory. But nursing my self-inflicted abrasion caused in collaboration with Cecilia's menacing walls, and looking at the silvery, seemingly calm surfaces of her drawings, I wonder if not the haptic – touch – is equally effective when it comes to stoking rememberance. I exited the gallery suddenly recalling the walls of my school corridors. Textured, hard, but smoother than the ones at Destiny's. Maybe the walls were sanded down over time by the friction between the school's architecture and the bodies of thousands of pupils slamming against them.